Unequal Exchange

The world economy is characterized by a large net flow of goods and resources from the global South to the global North through a process known as “unequal exchange”. This dynamic is a major driver of impoverishment and inequality.

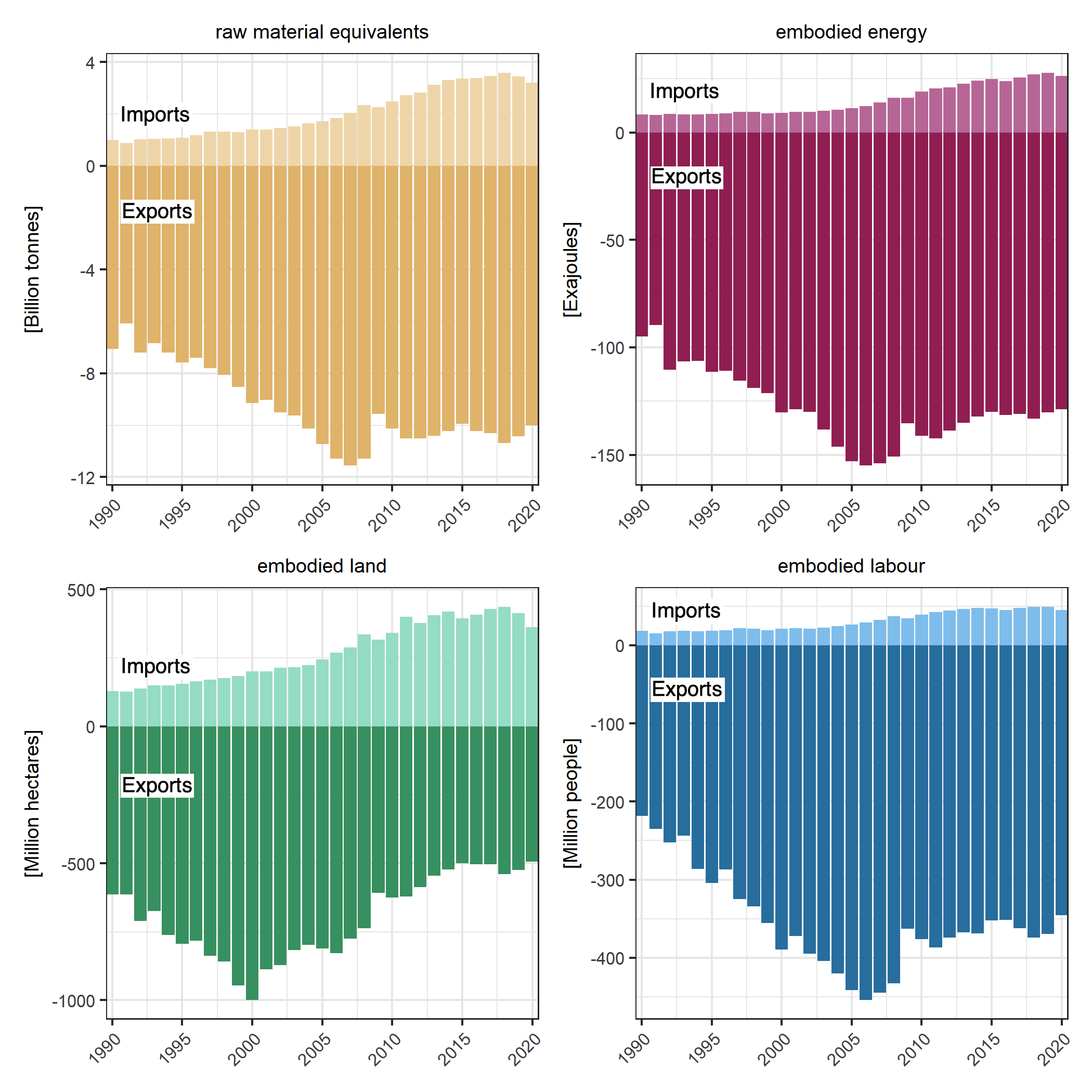

Growth and capital accumulation in the core relies on a large net-appropriation of resources and labour from the global South through unequal exchange in international trade. This pattern has been described by world-system theorists, mostly from the global South, including Samir Amin, Ruy Mauro Marini and Arghiri Emmanuel.1 Unequal exchange occurs because core states and firms leverage their geopolitical and commercial power to compress wages, prices and profits in the global South, both at the level of national economies as well as within global commodity chains, such that Southern prices are systematically lower relative to Northern prices.2 North/South price inequalities are very large and substantially exceed productivity differences. This means that the South is compelled to export large quantities of goods to the North in order to pay for any given level of imports, as this graph illustrates.3

The South’s physical imports and exports

Source: Hickel, Dorninger, Wieland & Suwandi, Global Environmental Change (2022), updated with GLORIA to 2020.

Unequal exchange results in large net flows of resources from South to North each year. These resource flows are mostly embodied in manufactured goods and services. On average, from 1990-2020, the North has net-appropriated 7.3 billion tons of embodied raw materials, 113 Exajoules of embodied energy, 427 million hectares of embodied land, and 323 million person-years per year.

This drains the South of resources that are necessary for development, perpetuating impoverishment.4 These productive capacities could be used to meet human local human needs, but instead they are appropriated to service capital accumulation in the core. For instance, the energy and materials appropriated each year is more than what is required to bring the whole population of the global South up to decent living standards, but instead it is used to produce fast fashion and tech gadgets for global commodity chains, supporting growth and consumption in the North.

This pattern also means that while the global North benefits from the additional resources, the ecological impacts are suffered in the South. The damages are “externalized” to the world’s most vulnerable communities.

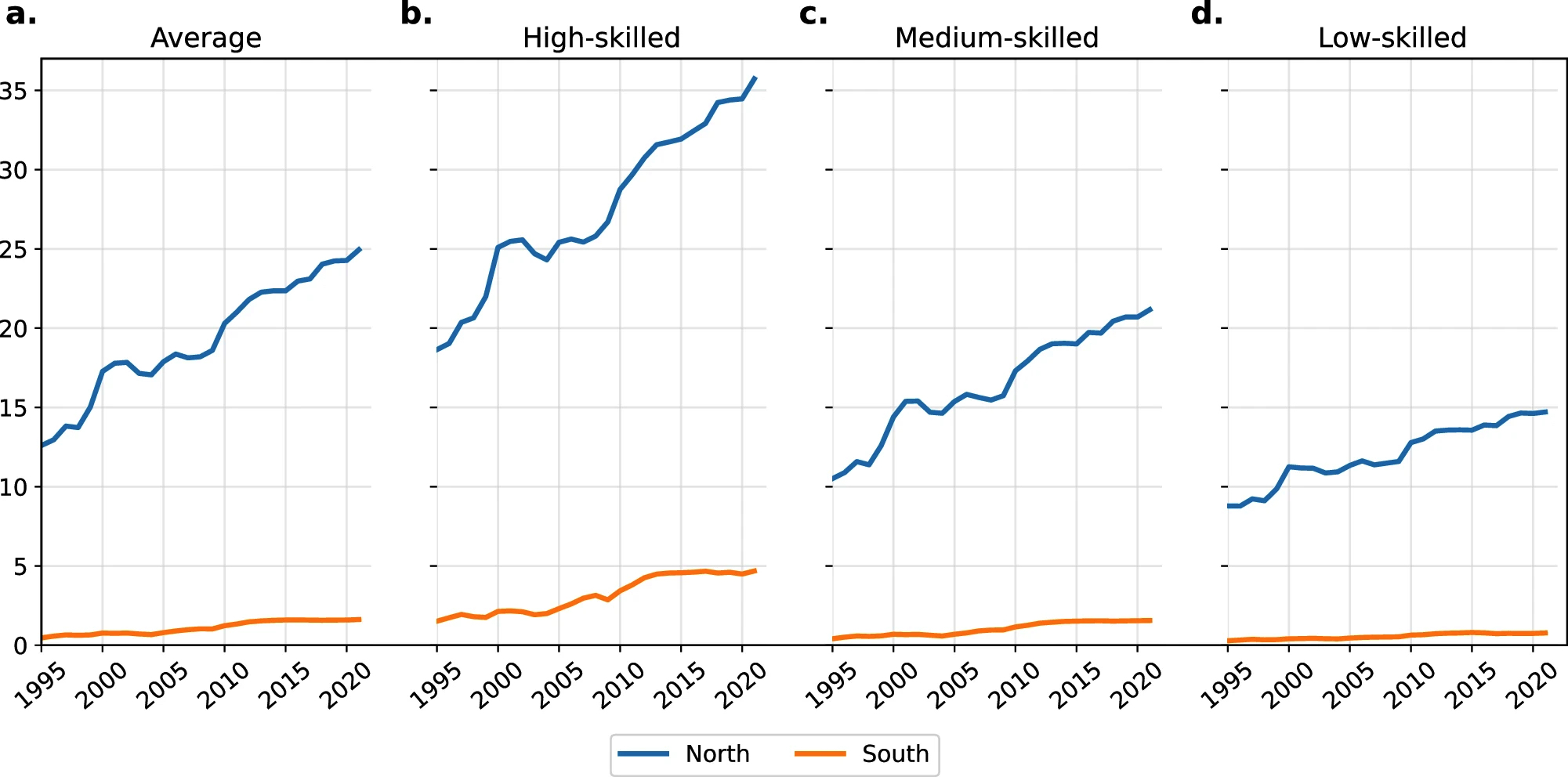

This graph shows Northern net-appropriation of Southern labour using a different dataset that divides by skill level and sector (via the dropdown menu). Over the period 1995-2020, Northern appropriation averaged over 600 billion hours per year. This is similar to the total labour rendered by all workers in the US and EU combined.

In the past, some analysts have assumed that unequal exchange of labour occurs because the global South exports large quantities of low-skill labour in primary sectors in exchange for smaller quantities of high-skill labour in secondary and tertiary sectors. However, this data shows the North net-appropriates labour across all skill levels and all sectors. In fact, more labour is appropriated in manufacturing and services than in agriculture and mining combined.

One way to represent the scale of this labour is in terms of its wage value. The menu option displays the wage value of the net-appropriated labour in terms of Northern wages as well as global average wages, by skill level. If Northern workers were to perform the net-appropriated quantity of labour domestically, it would cost €16.9 trillion in terms of wages.

These patterns of unequal exchange contribute substantially to increasing aggregate consumption in the global North. As this graph shows, more than a third of all labour consumed in the global North is net-appropriated from the global South. Something similar is true for materials, visible using the dropdown menu. In other words, if imperialist appropriation was to end, the core economies would have their consumption reduced very substantially. If they wanted to maintain existing levels of consumption, they would have to increase their domestic material extraction and domestic working time.

Unequal exchange is driven in large part by wage inequalities. Global wage inequalities are very large, and wage gaps are getting larger. Southern wages are 87–95% lower than Northern wages for work of equal skill. This is not due to sectoral differences. Recent research shows that Southern wages are 83–98% lower than Northern wages for work of equal skill within the same sector. These large wage inequalities cannot be explained by productivity differences. They result from imperialist dynamics in the world economy that act to suppress wages and consumption in the global South. For instance, the imposition of structural adjustment programmes during the 1980s and 1990s cut public employment, removed labour rights and wage regulations, and imposed downward pressure on real wages, exacerbating North-South wage differentials.

Wage trends in the global North and South

Euros per hour (Constant 2005 EUR)

Source: Hickel, Hanbury Lemos, Barbour, Nature Communications (2024).

This graph shows the South’s exchange ratios with the global North over time, as exports divided by imports. We can see that in 1990 the South had to export 7 tons of materials to the North for every 1 ton it imported. During the period 2005 to 2015, that ratio declined substantially. The same is true for energy and land. This improvement in the South’s position is due in large part to the commodities boom that improved Southern export prices (and is also due in large part to development and industrial upgrading in China). This is in large part what has driven the decline in the North’s total net-appropriation from the South during this period, which has in turn constrained Northern consumption. This provides some hope that trade is moving in a more equitable direction, although progress seems to have slowed in the final years of this dataset.

The dynamics of unequal exchange described on this page help explain the persistence of inequality in the world economy (see our entry on global inequality). Economists often assume that the global South is “behind”, and will be able to follow the same development trajectory as rich countries, eventually catching up to them. But catch-up development cannot occur within a system that is predicated on imperialist appropriation. It physically cannot occur in the context of net South-North flows. This is why the income gap between the global South and global North has continued to increase since the end of colonialism. There is no catch-up development happening. This is not because poor countries are “behind”. It is because they are exploited.

Notes

Suggested citation: Hickel, J., Hanbury Lemos, M., Barbour, F., Mao, X., Sullivan, D. & Zoomkawala, H. (2025). “Unequal exchange”, Global Inequality Project. Accessed at: https://globalinequality.org/unequal-exchange

1. Amin (1976), Marini (1973), Emmanuel (1972), Bunker (1985), Ricci (2021).

2. Wallerstein (2004), Chomsky (1993), Smith (2016), Suwandi (2019), Clelland (2014).

3. Hickel, Dorninger, Wieland & Suwandi (2022), Hickel, Hanbury Lemos & Barbour (2024).

4. Rodney (1972), Galeano (1971).

References

Amin, S. (1976). Unequal development: An essay on the social formations of peripheral capitalism. Harvester Press.

Bunker, S.G. (1985). Underdeveloping the Amazon: Extraction, unequal exchange, and the failure of the modern state. University of Illinois Press.

Chomsky, N. (1993). Year 501: The conquest continues. South End Press.

Clelland, D.A. (2014). The core of the Apple: Degrees of monopoly and dark value in global commodity chains. Journal of World-Systems Research 20(1), pp. 82-111.

Emmanuel, A. (1972). Unequal exchange: A study of the imperialism of trade. Monthly Review Press.

Galeano, E. (1971). Open veins of Latin America: Five centuries of the pillage of a continent. Monthly Review Press.

Hickel, J., Dorninger, C., Wieland, H., & Suwandi, I. (2022). Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global south through unequal exchange, 1990–2015. Global Environmental Change, 73, 102467.

Hickel, J., Hanbury Lemos, M., & Barbour, F. (2024). Unequal exchange of labour in the world economy. Nature Communications, 15(1), 6298.

Hickel, J., Sullivan, D., & Zoomkawala, H. (2021). Plunder in the post-colonial era: Quantifying drain from the global south through unequal exchange, 1960–2018. New Political Economy, 26(6), 1030-1047. [PDF]

Marini, R.M. (1973). Dialéctica de la dependencia. México DF: Ediciones Era.

Rodney, W. (1972). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Bogle-L’Ouverture.

Ricci, A. (2021). Value and unequal exchange in international trade: The geography of global capitalist exploitation. Routledge.

Smith, J. (2016). Imperialism in the twenty-first century: The globalization of production, super-exploitation, and the crisis of capitalism. Monthly Review Press.

Suwandi, I. (2019). Value chains: The new economic imperialism. Monthly Review Press.

Wallerstein, I. (2004). World-systems analysis: An introduction. Duke University Press.